Nice old photos of The Forester’s Arms, currently know as the All Inn One

and the Forest Hill Hotel, including floor plan).

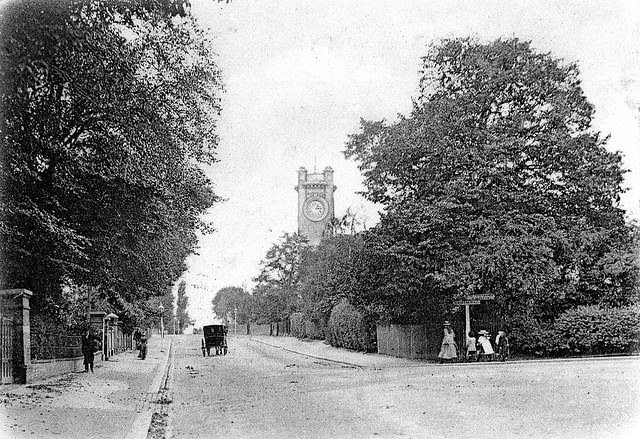

Forest Hill Station

1910

1911

Some film from 1964 driving up from Lordship Lane to junction with South

Circular then down into Forest Hill and round under the railway bridge.

You may notice there are works happening down London road… nothing much changes eh?

(link takes you to relevant bit @ 3:10 ish but there may be more you notice)

From Facebook. 1971 apparently.

I saw this pic the other day which I thought was gorgeous. 1960 apparently

Here’s a blast from the past - Spiggy’s on Dartmouth Road

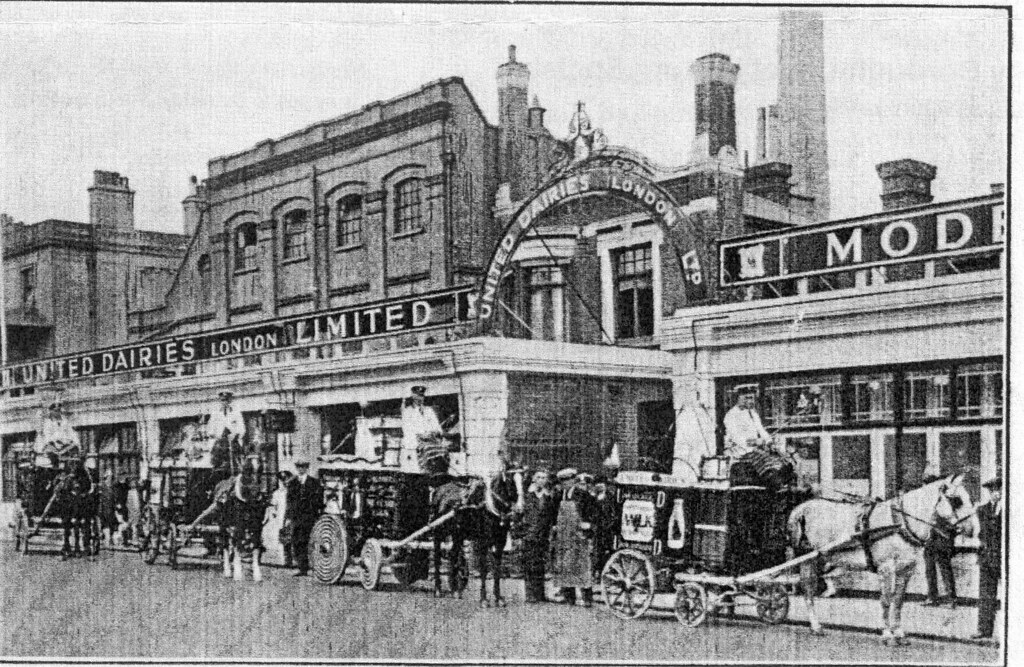

Here you go, it became a Dairy in 1927:

An old favourite!

In the 1870’s the Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro painted Lordship Lane station from the bridge in Sydenham Hill Woods looking north at the Crystal Palace High Level Railway. What was open countryside then is all overgrown now, but there are a few visible pointers to the old railway track.

I’ve led walks for friends along the railway route from Nunhead to Crystal Palace a couple of times. Here’s an overlay of some current views with the painting to compare. The accuracy of his drafting, of the landscape and especially of the houses that are still there is, as you might expect, excellent.

In his painting, centrally we see the railway line, then the station

buildings, just beyond them was a bridge over Lordship Lane heading into

the current Horniman

Nature Trail, at the back of Woodvale. To the right in the distance we

see the hill on which Horniman Gardens now stand. In the near right

foreground now stand the apartment blocks of the Sydenham Hill Estate.

Finally, left of centre, the red house with the cream house left of it

on the corner of Woodvale.

this pic appeared on Twitter recently, the original wooden bridge from which Pissarro painted Lordship Lane station. Don’t know the date - guessing around 1900 from the dress of the two children pictured?

Lordship Lane Station looking north in c. early 1920’s

Lordship Lane Station looking north in the early 1950’s

Photo from Brian Halford collection

Lordship Lane Station looking south during demolition in 1956

Photo by John L. Smith

The site of Lordship Lane Station looking north east in July 2007

Photo by Nick Catford

Aerial view showing the site of Lordship Lane Station - the platforms are shown in black. The arrow indicates the camera position and direction of the photograph above.

Click here for more pictures of Lordship Lane Station

Click here for pictures of Cox’s Walk footbridge south of Lordship Lane Station

Click here to see literature advertising the ‘Palace Centenarian’ - the last train

and this is one side of the station, a 2 storey building with steps up to platform level.